Dark-eyed Junco

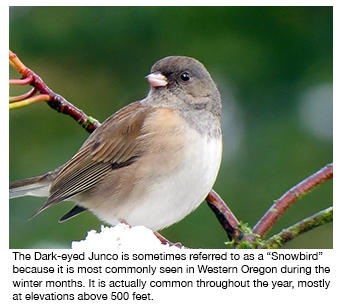

Juncos are familiar birds to most everyone, visiting yards from fall through spring. Small, with an all dark head, they have a pinkish bill and bold white outer tail feathers. Some people call them “snowbirds” because they are seen on the valley floor during the winter, but juncos are actually here throughout the year. During the breeding season, they move up from the valley floor, preferring elevations of about 700 feet or higher, so if you live in the foothills surrounding the valley, you may see them all year long. While they are prominent in suburban yards in winter, for breeding they prefer the cover of a small bush or clump of tall grass above their ground nests.

Juncos are familiar birds to most everyone, visiting yards from fall through spring. Small, with an all dark head, they have a pinkish bill and bold white outer tail feathers. Some people call them “snowbirds” because they are seen on the valley floor during the winter, but juncos are actually here throughout the year. During the breeding season, they move up from the valley floor, preferring elevations of about 700 feet or higher, so if you live in the foothills surrounding the valley, you may see them all year long. While they are prominent in suburban yards in winter, for breeding they prefer the cover of a small bush or clump of tall grass above their ground nests.

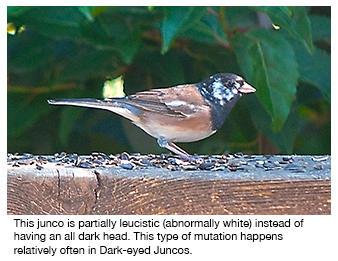

Officially known as Dark-eyed Junco, there are different plumage patterns across North America. Oregon’s form was once known as the “Oregon Junco” and birds of eastern North America were called “Slate-colored Juncos.” Long thought to be separate species, in the 1970s taxonomists decided all formed a large, diverse species named Dark-eyed Junco. In addition to plumage differences, habitat preferences and behaviors may vary and some such differences may have occurred as a result of conflict with human activities and urban expansion. Because of the number of observed changes, and how quickly these are occurring, the junco is now being extensively studied as a model for evolution.

Officially known as Dark-eyed Junco, there are different plumage patterns across North America. Oregon’s form was once known as the “Oregon Junco” and birds of eastern North America were called “Slate-colored Juncos.” Long thought to be separate species, in the 1970s taxonomists decided all formed a large, diverse species named Dark-eyed Junco. In addition to plumage differences, habitat preferences and behaviors may vary and some such differences may have occurred as a result of conflict with human activities and urban expansion. Because of the number of observed changes, and how quickly these are occurring, the junco is now being extensively studied as a model for evolution.

One example of evolutionary change is in a population in southern California. The Dark-Eyed Junco has always been a migratory species, present only in the winter in southern California. In the early 1980s that began to change. On the campus of the University of California in San Diego, a population of Dark-eyed Juncos remained through the winter and has become established as a non-migratory population. Now, Dustin Reichard, of Wesleyan University has documented females singing and doing so in a way that suggests they are keeping other females away from their male. Female singing is unknown for any other junco population in North America.

Juncos are one of the most numerous and well-known songbirds across all of North America, with numbers estimated at more than 630 million birds. Most juncos that breed in Oregon and further south are non-migratory or move only very short distances, often just a change of elevation, but juncos to the north do migrate, although often not more than a few hundred miles. It is interesting to note that east of the Mississippi River, in migratory junco populations, females migrate farther south than do males. In Oregon, the winter population increases as a result of more birds moving in from more northern breeding areas, adding to the non-migratory population. Some of these visitors have different plumages than we usually see because they represent other races or forms.

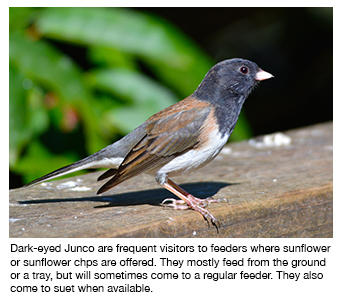

Nearly 75% of a junco’s diet consists of plant material, mainly seeds, with insects and spiders accounting for the remainder. Winter’s decreasing day length and lower temperatures stimulate juncos’ physiology to begin storing more fat, and the birds shift their diet to include more fats and proteins. Seeds with high oil content, such as black oil sunflower, and white proso millet tend to be preferred foods at this time, and fresh sunflower already out of the shell is often especially attractive. Small seeds require less time and effort to open and the high oil content makes the fats readily available. Juncos usually feed on the ground so even spilled Nyjer seeds may be eaten, although they are taken less often. They will also appreciate open water that you make available for them to drink. They normally drink from shallow pools or small streams, but these are sometimes frozen during especially cold weather.

Juncos typically hop rather than walk. Watch when they spread their tails and you will see a flash of white on each side from their white outermost tail feathers. This flash of white may serve to startle, or deflect, predators, but it may also be a way of communicating to other flock members. If a bird senses danger and dives into the brush, the white tail alerts others of the danger.

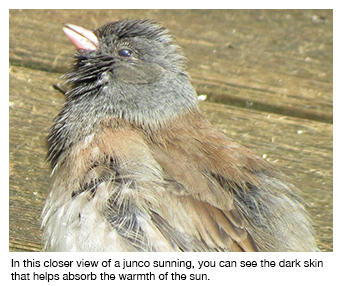

Researchers have studied juncos to help understand behavior and physiology of songbirds. For example, through work with juncos we better understand how day length causes changes to the birds’ reproductive systems. Once the day length exceeds 10 hours, juncos’ gonads rapidly enlarge and males increase their singing, establishing their breeding territories. Males have a long, rapid, and frequently repeated trill, often sung from an elevated perch. The female builds her nest on the ground and she alone incubates the clutch of eggs. After the young hatch, both parents feed and care for them. Since males sing from the trees, their foraging patterns and associated foods may differ slightly from those of the females who spend most of their time closer to the ground. A single brood per season is typical for birds breeding at higher elevations or among migratory populations since males often don’t arrive on breeding grounds until mid-May. Non-migratory birds have more time for breeding and often have 2 broods, with the first set of eggs being laid as early as mid-March to April.

Juncos may live to eleven years, so it’s likely that birds seen in your yard this winter may be the same individuals that visited last winter. Provide them with good cover, such as hedges or shrubs, but prune them to prevent cats from hiding underneath to prey on birds. With such protection on your part, juncos may become regular winter visitors to your backyard where you can easily observe and enjoy watching them.