Cedar Waxwings

Many people have a special fondness for Cedar Waxwings.. The soft plumage is delicate with subtle washes of color that most people find very attractive and they are non-aggressive, social birds

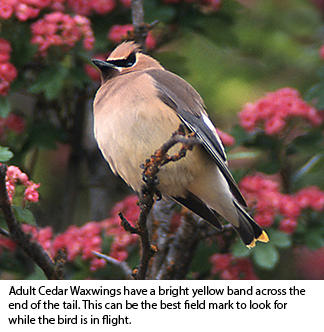

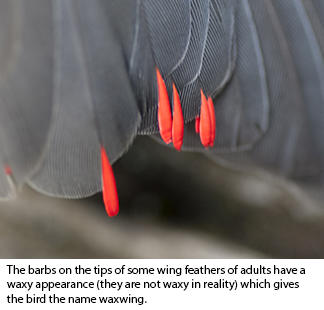

The Cedar Waxwing is not likely to be confused with any other bird found in Western Oregon. It has a prominent crest atop its head, silky gray-brown plumage with a pale rosy blush, a black mask across the face, and a bright yellow band across the tip of the tail. On many individuals, you may see small bright red spots of color on the wings when they are folded. These drops of red look waxy, hence the name “waxwing.” In reality, they are not wax, but simply thickened and fused barbs at the tip of the secondary feathers of the wing. As the birds grow older, these red tips become larger and probably serve as a sign of sexual maturity. The only similar bird in North America is the Bohemian Waxwing, but it is slightly larger, a bit more colorful, and winters in parts of Northeastern Oregon, but is very rare west of the Cascades.

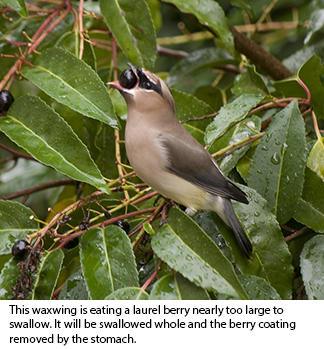

Cedar Waxwings are usually seen in groups of a few birds to more than 50, which wander widely throughout their range. A small flock may appear and then disappear a short time later if they don’t find the food that they seek. These birds are specialists, seeking sugary fruit, although many insects are caught and eaten during the summer. A wide variety of fruit is eaten throughout the year, especially in the winter. In addition to wild fruit, many exotic fruit is also eaten. Waxwings eat red osier dogwood, madrone, serviceberry, mountain ash, juniper berries, honeysuckle, and even Russian olive, mulberry and strawberries. Sometimes, a flock may find a cherry tree and completely strip the fruit, which can make them unpopular with the individual who planted the tree, but they seldom do significant damage to commercial crops. Their dependence on sweet fruit is what dictates waxwings’ wandering habits. They are always on the move, stopping to feed as they find fruit, then moving to the next food source. As a result, you may only occasionally see waxwings in your yard.

Waxwings make a high-pitched, thin tzeeeeee, but have no true song. Song helps with defining and defending territory in most birds, but since Cedar Waxwings don’t establish a territory, they have nothing to defend. They don’t nest colonially, but they seem to have little objection to another pair of waxwings building a nest nearby. Pairs do separate from the flock during breeding, but will re-gather shortly after the young have fledged. Successful mates often stay together in subsequent seasons.

Waxwings make a high-pitched, thin tzeeeeee, but have no true song. Song helps with defining and defending territory in most birds, but since Cedar Waxwings don’t establish a territory, they have nothing to defend. They don’t nest colonially, but they seem to have little objection to another pair of waxwings building a nest nearby. Pairs do separate from the flock during breeding, but will re-gather shortly after the young have fledged. Successful mates often stay together in subsequent seasons.

Cedar Waxwings are one of our latest nesting birds. Nest construction and egg laying are seldom begun before late June or early July. They wait until there is a good supply of summer-ripened fruit available for their young when they fledge. A good supply of insects is also necessary because insects are the primary diet when the young birds are growing and developing as nestlings. A second brood is often raised, making it late August before some young have fledged. Newly fledged birds lack the mask over the eyes, azure gray and have pale streaks on the breast.

Cedar Waxwings are one of our latest nesting birds. Nest construction and egg laying are seldom begun before late June or early July. They wait until there is a good supply of summer-ripened fruit available for their young when they fledge. A good supply of insects is also necessary because insects are the primary diet when the young birds are growing and developing as nestlings. A second brood is often raised, making it late August before some young have fledged. Newly fledged birds lack the mask over the eyes, azure gray and have pale streaks on the breast.

“The Polite Bird” and other similar names have sometimes been applied to the Cedar Waxing. Some of their behaviors imply courtesy and politeness to us. It is not unusual to watch waxwings passing fruit between individuals. Four or five birds may sit side-by-side on a branch, and when another arrives with a berry in its mouth, instead of eating the berry, it may offer it to the adjacent bird. That bird in turn may pass it to the next individual and so on. We may never know what is really behind this behavior, but it seems gentle and courteous to our eyes.

The passing of food (or sometimes, an inanimate object) is also an important aspect of Cedar Waxwing courtship rituals. A male will bring food and land next to his mate, turning his head sideways and offering her his treat. She usually accepts and hops sideways along the branch away from him. Then she hops back and gives him back the fruit. He then hops away, sometimes seeming to bow first, then hops back and gives the food back to her. This may happen several times before the female finally eats the fruit. It is easy to see why we relate so positively to these birds. Nothing about them seems aggressive, either to others of their kind or to other birds sharing their surroundings. However, if you were to watch long enough, you might see a minor squabble between nearby males during the breeding season. Such spats are short-lived and relatively minor when compared to fights between individuals of other species.

Waxwings can survive for several months on a diet of sugary fruit, but there are some risks. First, they must wander in search of a good crop to feed on. But there is another hidden danger. Sugary fruit sitting in the hot sun can ferment and convert some sugar to alcohol. Over-eating such fruit has actually caused the death of some waxwings, but more often the danger is temporary—the birds simply become intoxicated. John James Audubon was apparently able to sketch and draw waxwings that he picked up off of the ground in this condition. All birds have high metabolisms and recovery is usually fast, but it can put them at some risk of being caught by predators. It also means that you must take extra care if waxwings are feeding on an abundance of fruit, like laurel berries, commonly found in yards. When the birds take flight, they sometimes are too “drunk” cannot maneuver quickly and they may strike your windows more than at other times. You may need to be extra diligent to prevent this and to prevent the birds from being caught

Waxwings can survive for several months on a diet of sugary fruit, but there are some risks. First, they must wander in search of a good crop to feed on. But there is another hidden danger. Sugary fruit sitting in the hot sun can ferment and convert some sugar to alcohol. Over-eating such fruit has actually caused the death of some waxwings, but more often the danger is temporary—the birds simply become intoxicated. John James Audubon was apparently able to sketch and draw waxwings that he picked up off of the ground in this condition. All birds have high metabolisms and recovery is usually fast, but it can put them at some risk of being caught by predators. It also means that you must take extra care if waxwings are feeding on an abundance of fruit, like laurel berries, commonly found in yards. When the birds take flight, they sometimes are too “drunk” cannot maneuver quickly and they may strike your windows more than at other times. You may need to be extra diligent to prevent this and to prevent the birds from being caught  by cats wandering in your yard. Soon, they will have stripped the berries and move on. It may be months or even a year before you see many of them in your yard again, but we usually feel it is worth the wait. Small fruits may look ripe to us but be ignored by the birds. Just a week or more later, they are devoured by the birds, yet they look the same to us. The birds are waiting for the fruits to be fully ripe containing the maximum amount of sugar. How do the birds know when full ripeness has occurred? The birds have little or no sense of smell, so that is not the answer. The key is how the fruits look, which is different to the birds than it is to us. Most birds see ultraviolet light which we do not see. As the fruits ripen, they begin to reflect ultraviolet light and this is the cue the birds use to know when the fruits are becoming ripe.

by cats wandering in your yard. Soon, they will have stripped the berries and move on. It may be months or even a year before you see many of them in your yard again, but we usually feel it is worth the wait. Small fruits may look ripe to us but be ignored by the birds. Just a week or more later, they are devoured by the birds, yet they look the same to us. The birds are waiting for the fruits to be fully ripe containing the maximum amount of sugar. How do the birds know when full ripeness has occurred? The birds have little or no sense of smell, so that is not the answer. The key is how the fruits look, which is different to the birds than it is to us. Most birds see ultraviolet light which we do not see. As the fruits ripen, they begin to reflect ultraviolet light and this is the cue the birds use to know when the fruits are becoming ripe.

Cedar Waxwings are attractive and well-loved birds. They are difficult to attract to your yard, but fruit bearing bushes and trees are often one way of attracting them at certain times of the year. If they come, you will be well-rewarded for you efforts.