European Starling — Loved in Europe, hated in North America

European Starlings may be one of the most disliked bird species in North America, especially by birders. Even their name is often misunderstood. They are known to science by the Latin Sturnus vulgaris. For many of us, “vulgar” has a negative meaning, but in fact, it simply means “common,” as this is the common starling of Europe. “Sturnus” and starling mean the same thing: “little star.” The reference to star most likely comes from their silhouette in flight, as their long pointed beak, outstretched, triangle-shaped wings, and short tail somewhat resembles a star shape.

European Starlings may be one of the most disliked bird species in North America, especially by birders. Even their name is often misunderstood. They are known to science by the Latin Sturnus vulgaris. For many of us, “vulgar” has a negative meaning, but in fact, it simply means “common,” as this is the common starling of Europe. “Sturnus” and starling mean the same thing: “little star.” The reference to star most likely comes from their silhouette in flight, as their long pointed beak, outstretched, triangle-shaped wings, and short tail somewhat resembles a star shape.

Starlings belong to a large, Old World family that also includes mynas, and, unlike the European Starling, some starling species have spectacular plumage. In Europe, Africa and southeast Asia, 114 species of starlings exist but the family name, starling, comes from the plain-colored European Starling that was introduced into North America. Once they began to flourish here they have probably played a significant role in the decline of some of our native birds.

European Starlings are well known for their vocal ability, mimicking calls and songs of many other birds, often quite accurately. Mozart had a pet starling that he was very fond of, which amused him by being able to sing a short selection of his music. Mimicry of human speech by starlings was reported in the works of Aristotle, Pliny and the ancient Romans. Shakespeare also knew of this ability, for in Henry IV (Part I), Hotspur threatens to train a starling to say the forbidden name “Mortimer” just to annoy the king. In fact, it is this Shakespearian reference that is indirectly responsible for the successful introductions of starlings into North America.

In the late 1800s, many species of European birds, including European Starlings, were introduced in the United States and Canada but most of these failed. Among the places European Starlings were released was in Portland, Oregon in 1889 and 1892, by the Portland Song Bird Club. By 1902, all of the birds released in Portland had disappeared, as did most such birds released around the country. Then, in 1890, Eugene Scheiffelin, of the American Acclimatization Society, released 60 starlings in New York City’s Central Park, followed by 40 more the next year. His stated purpose was to introduce into the United States every bird mentioned in Shakespeare, and that single reference in Henry IV was the reason he released the starlings. The birds from those two introductions succeeded where no others had, and in less than a century, European Starlings spread across the continent. They became common in western Oregon by the early 1960s, and the North American population is now estimated to be over 200 million, approximately one third of the world’s population.

In the late 1800s, many species of European birds, including European Starlings, were introduced in the United States and Canada but most of these failed. Among the places European Starlings were released was in Portland, Oregon in 1889 and 1892, by the Portland Song Bird Club. By 1902, all of the birds released in Portland had disappeared, as did most such birds released around the country. Then, in 1890, Eugene Scheiffelin, of the American Acclimatization Society, released 60 starlings in New York City’s Central Park, followed by 40 more the next year. His stated purpose was to introduce into the United States every bird mentioned in Shakespeare, and that single reference in Henry IV was the reason he released the starlings. The birds from those two introductions succeeded where no others had, and in less than a century, European Starlings spread across the continent. They became common in western Oregon by the early 1960s, and the North American population is now estimated to be over 200 million, approximately one third of the world’s population.

European Starlings are very aggressive birds when it comes to nest competition. They nest in cavities and will aggressively drive out other native cavity-nesters including birds larger than themselves. They compete with bluebirds, swallows, woodpeckers and will even drive Wood Ducks out of boxes or cavities. Both the Eastern and Western Bluebird do not fare well in competition with starlings. This aggression toward native birds is probably what has been the cause of so much loathing on the part of birders, and some would like to see starlings destroyed.

Forests and wild natural habitats are not conducive to success of European Starlingsk. This is probably why most early introductions failed: there were simply no suitable places for starlings to live. By the time the last 100 birds were released, the region was much more urbanized and starlings did well. They took to nesting in cavities provided by buildings as they are more tolerant of human activity than most native species. As the human population of North America increased and European influence spread across the country, landscapes were altered, favoring starlings over native species.

Despite their bad reputation, starlings may actually be beneficial to some agricultural operations because they devour large quantities of snails, cutworms, beetles and other invertebrates that destroy domestic crops. However, in large numbers they can be problematic, and in the fall and winter, they compete with native birds for wild fruits and grains. If certain foods become limited in their chosen habitat, they easily switch to another available food source, and some native species are less adaptable.

Despite their bad reputation, starlings may actually be beneficial to some agricultural operations because they devour large quantities of snails, cutworms, beetles and other invertebrates that destroy domestic crops. However, in large numbers they can be problematic, and in the fall and winter, they compete with native birds for wild fruits and grains. If certain foods become limited in their chosen habitat, they easily switch to another available food source, and some native species are less adaptable.

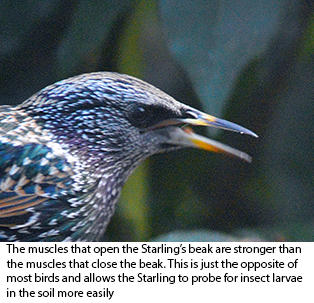

From a biological perspective, they are very interesting birds. Unlike most birds, the muscles that open their beak are stronger than the muscles that close it. This allows them to open their mouths and easily spread the blades of short grass when foraging in fields or to easily probe into soft soil. During the breeding season, males bring plants, such as yarrow, to the nest cavity and weave them into the nest. Chemicals in these plants stimulate the immune systems of the hatchlings, increasing their likelihood of surviving.

As fall approaches, starlings molt and their new buffy-edged feathers give them a speckled appearance. As the seasons progress, the tips of these body feathers wear away until by spring, they look shiny and iridescent. Thus, the shiny breeding plumage is the result of old, worn feathers. Males and females look nearly identical but there are subtle differences. The base of the male’s bill is pale blue and the base of the female’s bill is pale pink, although this can only be seen at close range. Recent research shows that the iridescent throat of the male looks different than that of the female when seen in ultraviolet light, which is easily seen by birds but not visible to humans. It’s possible that this may attract females, but we don’t know for sure.

European Starlings are here to stay, but you may wish to do all that you can to discourage them from being attracted to your yard. Avoid putting up nest boxes that will attract starlings. They cannot enter a hole smaller than 1.5 inches but this will also keep out some native cavity-nesters. Starlings do not eat seeds, so they are not attracted to your feeder (unless the seed becomes infested with insects) but they will come to suet feeders. A dome over a suet feeder may keep them out or you can use the type of suet feeder that is enclosed except for an open mesh on the bottom. Some such feeders have a roof-like cover, which further discourages starlings. Starlings don’t like to feed hanging from below such a feeder but chickadees, woodpeckers, bushtits and other birds will easily do so.

European Starlings may not be your favorite birds, but like everything else in nature, they are not really “evil” and do have some interesting qualities. They are here because humans brought them to this country and it is we who have altered the landscape to favor their proliferation. They will undoubtedly be with us for a very long time so let’s do what we can to minimize their impact on native species and appreciate the many qualities that we can learn from.